Op-Ed: The Myths of the Mighty Tool Watch

OpinionPublished by: Justin Mastine-Frost

View all posts by Justin Mastine-Frost

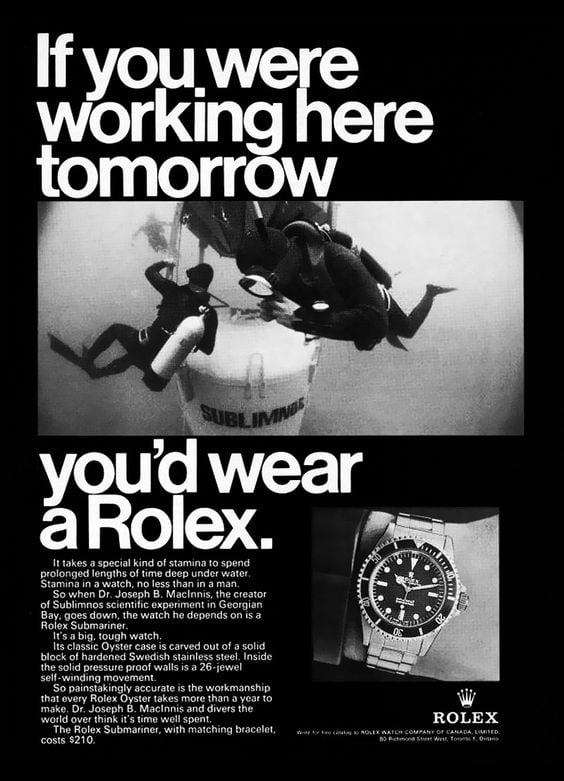

With slogans like “tested beyond endurance” and “instruments for professionals”, the watch industry loves to lean in on the rugged nature of tool watches. Whether we’re talking divers, field watches, pilot watches, or any other core category, there’s an overarching idea that luxury tool watches need to be capable of being dunked in acid and run over by a tank in order to be suitable for daily wear by a normal human.

That’s not to say there isn’t great marketing value to be had from dropping a watch down into the Mariana’s Trench or chucking one off of a modified weather balloon from the edge of space. I also don’t want to begrudge the idea of creating tools for actual working professionals in areas where reliable bulletproof tools are still necessary. For example, while Omega is quick to note that the Speedy is still NASA’s standard issue for astronauts, what they actually use as a tool in space is the X-33 quartz model (which is also standard issue, but never gets the spotlight). In contrast, Bremont’s MB series with Martin Baker — the fighter jet ejection seat company — is a particular shade of absurdist over-engineering. The ability to stay accurate while sustaining the g-forces of flight is cool, but in a plane dripping with cutting-edge tech, I doubt the thought of an ejecting pilot is “boy, I hope my watch is still accurate as my multi-million dollar craft splinters into little flaming bits.”

All this to say, marketing works, and the idea of certain specifications being mandatory for a tool watch has taken hold with a large portion of the collecting community. These are a few of the key areas where the need for over-engineering has been vastly overblown.

Magnetism

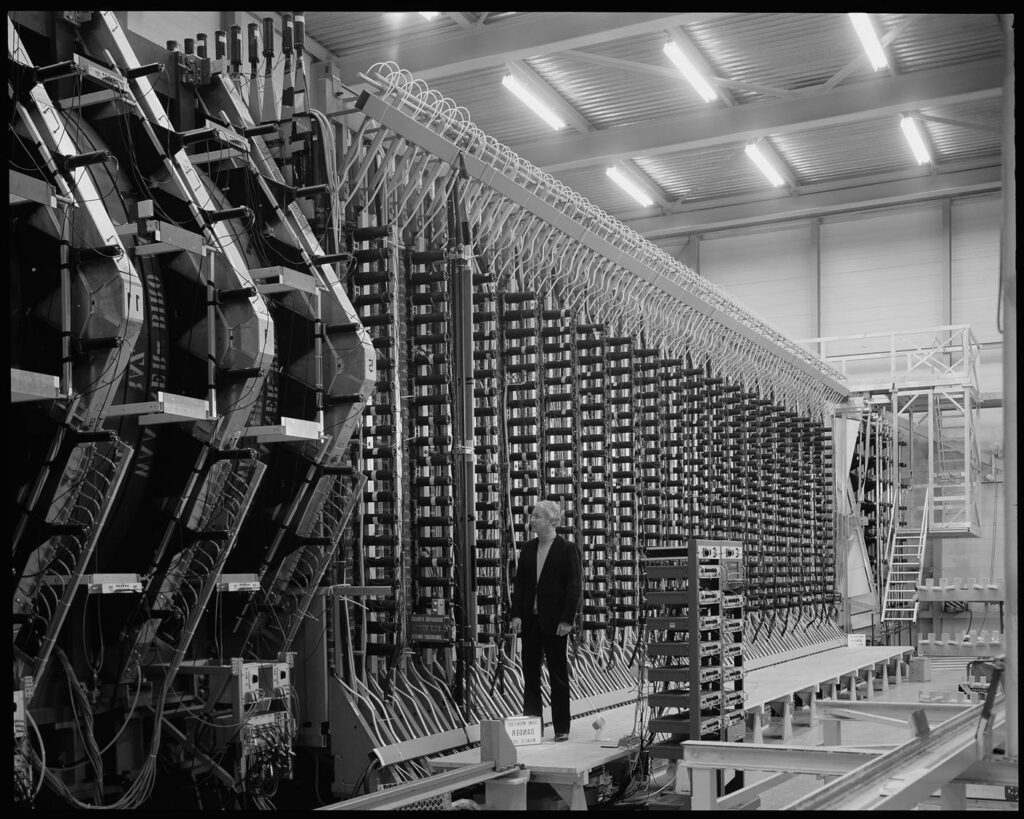

From the Aqua Terra to the Milgauss, there’s no shortage of models that have doubled down on the idea of a watch needing to have significant protection from magnetism. To be fair, yes, a watch CAN get magnetized in certain rare instances, but the instances in which it’s actually a legitimized fear are overblown. Yes, the Railmaster was made for early railway workers in an era when early electrification was underway (large electric motors create potent electric fields when not shielded), and the Milgauss was built for the lab workers in CERN, who were using magnetism as a core component of particle physics research.

These days, the most magnetism an average human experiences is what comes out of their cell phone. Given how glued we are to our devices, you’d expect this to have been flagged if it were even remotely problematic for the accuracy of our watches. Shy of slapping your watch up against the back of the after-market subwoofer in the trunk of your car or against the magnet in the back of that Marshall half-stack (for the guitar players in the room), the need for your watch to be antimagnetic is rather overblown. What’s more, the use of silicon hairsprings in watches (even ones that don’t hang their hat on the anti-magnetic marketing) further negates this concern.

Water Resistance

Now, this one makes me laugh… Every. Damn. Time. Whenever someone chimes in with a “for a modern diver I expected at least 200m of water resistance”, a small part of my soul dies. Lake Erie is 64 meters deep, and the deepest darkest corner of Lake Superior goes down a whopping 406 meters. So, should someone find that specific spot and accidentally cast their Omega Planet Ocean overboard, it would still be dry and running all the way down at the bottom (with almost 200 meters to spare!). But here’s the thing: who’s going down there? A recreational diver?

For the non-divers in the room, guess how deep a recreational diver is certified to dive. It must be at least half way to the average dive watch rating, right? Nope. It’s 40 meters.

I’ll take this one step further by raising another important figure: 332.35 meters. In a land filled with 500+ meter rated dive watches, no human on earth has ever completed a successful dive below 332.35 meters — at least not without being encased in a submersible. So, remind me again of the relevance of the Sea-Dweller aside from it being interesting as an engineering exercise?

Now before you try lecturing me on why you think you need 200m to be a proper dive watch, let me on one hand remind you of the premise of idiot-proofing, and on the other let me encourage you to take a real hard think of the last time your watch got wet and in what context that happened. The sink? The pool? Maybe a bit of snorkeling on vacation where at most you dropped down 15-20 feet below the surface? Were you trying to set the time while doing it? Probably not, so at a bare minimum there were a handful of gaskets doing their job and keeping the insides of your watch nice and dry, which brings me to our final culprit.

The Screw-Down Crown

I’ll be the first to admit that I’ve fallen for this one in the past, and depending on the task, it’s still something I prefer, but the screw-down crown is another feature that is mostly fueled by fear mongering. The general misconception is that gaskets are less effective when not secured, or that you’ll somehow clip something or catch something that will pull the crown of your watch out and let water come flooding in. For starters, the gasket systems of push/pull crowns can easily be sealed for 200m or more of water resistance (trusting your watch hasn’t been left unserviced for a decade). The original Blancpain Fifty Fathoms — an actual professional diver’s tool — didn’t have a screw-down crown, and its influence still echoes through the industry to this day.

I’ll also share another little tidbit of personal experience where I set out to test my own comfort boundaries. Two years ago I had the chance to go out surfing in Biarritz with the fine folks at Breitling. An eager and enthusiastic surfer, though certainly not a good one, I wanted to stay “on brand” for the occasion, so over my wetsuit went my Breitling Superocean ’57 Pastel Paradise Rainbow. The smaller of the rainbow series, it was only rated to 100m with a crown that didn’t screw down; my logic was that if something were to go wrong, I would hand it off to my Breitling contact and suffer the consequences of my poor decisions.

A solid half day in the water, repeatedly getting tossed around, faceplanting, and nearly breaking my nose a second time, the Superocean surfaced in far better condition than I. It continues to run perfectly on time, with not even a scratch, let alone any sign of water ingress. Did I just get lucky? Maybe. Will I ever get hung up on the “tough guy” marketing of watches ever again? Not a chance.

Previous Article

The Best Small Watches for Men

Next Article

Engineering As Art: The H. Moser & Cie. Pioneer Cylindrical Tourbillon Ref. 3811-1200

Join 75,000+ Other Watch Enthusiasts

Get our new arrivals first.